We say it‘s the nature of things

Noa Yekutieli

At the end of a taxi ride during Operation Guardian of the Walls last May, the driver concluded his conversation with artist Noa Yekutieli, revolving around the complex Israeli-Palestinian reality, by saying: ”There is nothing to do about it — it’s the nature of things“ This sentence accompanied Yekutieli for quite some time, along with the thought of those worldviews that we adopt as windows that are shuttered against the reality raging outside. Here, in Inga Gallery, she breaks through the walls with the help of nine imaginary windows and allows reality to penetrate.

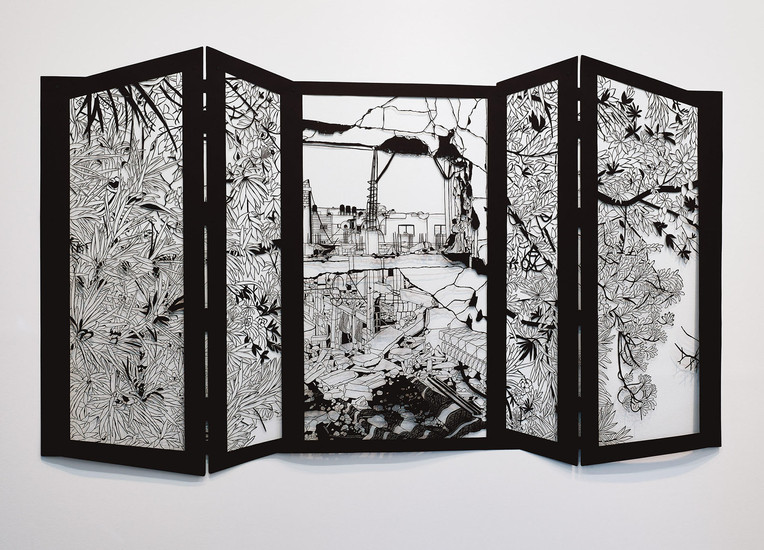

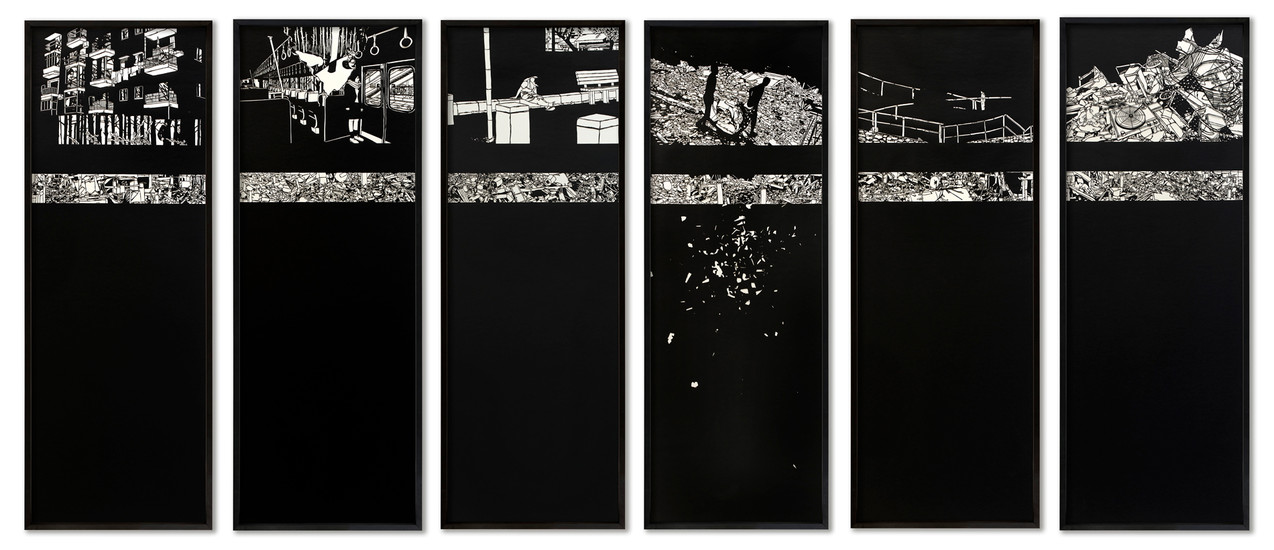

Since the publication of the treatise ”On Painting” in 1435, where architect and theorist Leon Battista Alberti instructed painters to make their painting a window onto reality, artists have been faced with the question of onto which reality to open a window. Yekutieli's windows are opaque black paper, which she perforates and ventilates in the studio for hours on end with delicate craftwork. The black surface slowly fades into contours full of beauty, and the result is black lace imagery, attractive, seductive, difficult to look away from.

Yekutieli chose not to open all the windows wide. Although the world outside is ostensibly visible to us, the glass panel is covered with a flora covering as a kind of lattice that challenges one’s gaze, and it takes time for the eye to focus and to discern what is revealed behind it. And what is reflected to the eye is not simple at all: peeking through the tangle of branches with their lush foliage are images of ruins, crumbling buildings, and piles of stone — images taken from photographs of destruction caused by bombing during the recent operation in Gaza. And all this richness, which includes shocking images, is actually an imaginary space created with beauty by the gradually cutting out more of the black paper with infinite delicacy.

What helps the eye to focus its gaze and understand the imaginary space in front of it is Yekutieli's meticulous use of the rules of linear perspective, also formulated in the 15th century by Renaissance artists. This method is based on mathematical tools to create the illusion of distance and depth in a two-dimensional substrate. Yekutieli manages with great virtuosity to create sharp foreshortenings on the paper surface and offer the viewer the fleeting sense of standing in front of a three-dimensional architectural element. The scientific perspective is based on the perception of space geometrically from a single point of view, from which imaginary diagonal lines are drawn between the objects depicted in space, diagonals that meet at an imaginary point known as the vanishing point. The linear perspective has established itself in Western culture as a predominant way of representing reality, although it is not the way the human eye actually sees. It is a theoretical tool that is meant to impose mathematical law on space, a tool that, while founded on a complex reality, finds a single vanishing point, as if to say, “This is the nature of things.”

It is possible that the artist’s multicultural background, as the daughter of a mother of Japanese descent, enabled her to perceive the Western fixation and offer other ways of looking at reality. In traditional Japanese art, it is common to describe the illusion of depth in a totally different way, one that offers several different points of view rather than a single one. The Japanese artists left an empty space between the objects on a painted surface that isolated them, and this very composition created the illusion of distance between them. Another common way was to depict one object up close and large with all the other objects in the space reduced in relation to it. But while in Western art the background was traditionally portrayed as vague and blurred in relation to what was happening in the foreground, in Japanese art, perspective is depicted with the same sharpness as the object in front. For Yekutieli, too, what is reflected outside is just as important as the window itself. Her life circumstances as a new immigrant to Israel and then as an immigrant to the United States led her to adopt a flexible and dynamic point of view: capturing reality each time from a new and different perspective. In this body of work, she combines the different approaches to the depiction of space and allows us to look at what can be seen from different perspectives. She proposes that we examine our own point of view and reveals to us that perspective can be much more flexible.

As part of the entrenchment of the scientific perspective in our world, using techniques of measurements that gauge and examine the world with scientific tools, it is customary to offer people to examine the situation judiciously — “to get perspective”, to take a step back in order to see the whole picture. Yekutieli — to whom distances are not foreign – suggests that we get closer, go into the details, and notice the similarities and differences between the flora patterns and the images of the pattern of destruction. That we experience the beauty of nature as well as the aesthetics of destruction.

Her way of working on the papercuts begins and ends with a long session in the studio in front of the black surface, when using a knife she listens to the paper and chooses what to cut out and what to leave. She must remain physically close to the paper in order to feel how much she may cut out while leaving the frame intact. Only at the end of the work does she, like us, see the whole picture in its entirety. She offers us an invitation to see reality precisely and to train the muscles of seeing up close. To choose to delve into the details. And this is not a simple art: the flora patterns, taken from her nature photographs, which she creates on the glass panels of the windows, screen and obscure reality as a kind of camouflage net. Camouflage is used commonly in the natural world for survival by both prey and predators. And what if out of our desire to survive, we have forgotten to take off our camouflage uniforms? In her windows she skips between the different perspectives and requires the viewers to engage with the art of observation: to get closer, to move back, to look at the spaces between objects no less than at the objects themselves, to be active, to choose perspectives, and to change them again and again. As we browse through the gallery, we discover how much effort we need to muster for the act of observation, how demanding and arduous it is.

From the dawn of history, the window has carried with it a variety of symbolic meanings. It is a meeting place between inside and outside, between familiar and foreign. The window is, above all, potential: potential for the exchange of air and light, for becoming acquainted with the world outside, and at the same time for protection and bridging the different spaces, both in the outside world and in the inner world. Yekutieli allows us to choose whether to shut the window and remain protected in the sheltering beauty of nature or to dare to open the window wide and look directly at reality. In this series, she opens a window to complex realities and allows us to take a close-up look at what seems to be happening far away.

Shua Ben Ari