Since the Breath of Primeval Time [1]

Irit Hemmo, Gaston Zvi Ickowicz, Sharon Etgar

Since the Breath of Primeval Time [1]

Curated by Karine Shabtai

The ash is that which no longer exists, that has vanished like smoke, leaving behind nothing… the ash as memory of the fire; as memory. But – what has burned? Who? The ash does not reveal the answer. The ash is a closed secret, “being without a presence,” in Derrida’s terms. The veil of the ash will not be removed. Ash, being erasure, is the place of the nothing… Ash is destruction without possibility of restoration or re-turn; ashes as sign of the past to which no return is ever possible.

In her use of dust as a substance in her work, Irit Hemmo treats it in a way that recalls Derrida’s philosophical discussion of ash. Like the ash, dust too consists of a trace, testifying to a body which is no longer there. Hemmo collects her dust indoors, turning a vacuum cleaner into an inhaling- and exhaling- breathing machine. Then, back in the studio or at an exhibition space, she creates dust storms, blowing the dust over stenciled patterns made after images from local art history. Hence the images dismantled to be reproduced again, using dust particles. [2]

In a series of dust works she recreates a painting by Marcel Janco three times over, his 1949 Nocturne (death of a Soldier), which was part of the seminal Ofakim Hadashim show. Showing a soldier lying in shrouds, at the feet of his fellow soldiers in uniform, Janco seems to reference Picasso’s Guernica (1937) [3]. In title of the work, Untitled (After Marcel Janco) (2016), Hemmo both alludes to her precedent while exposing an attempted reproduction – or appropriation – that is doomed to fail. As the very substance consisting the image, the dust embodies the land of the place, the home, the nation and its soldiers, both fallen and surviving. However, as dust is hard to manage, the resulting image inadvertently distorts the original, ultimately reinterpreting it. Hence her tentative reproduction gives way to an archaeology of the image.

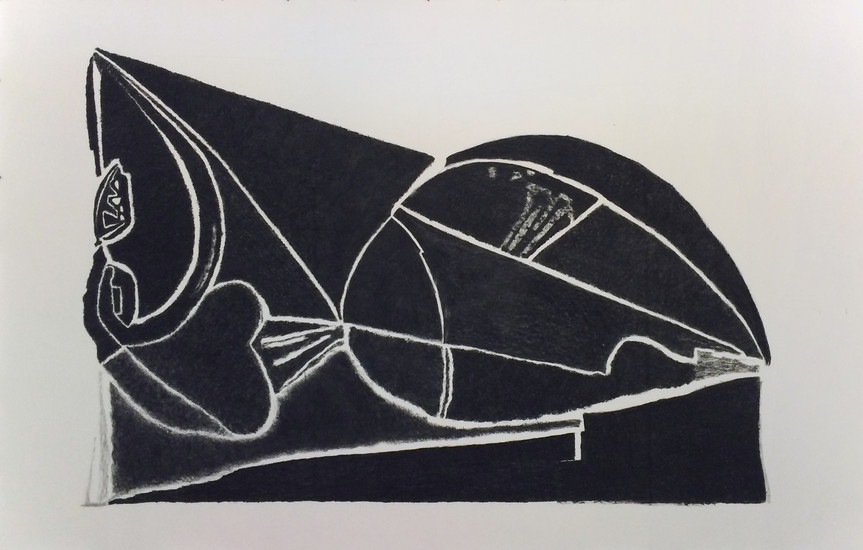

In an additional work, the charcoal drawing Untitled (After Aharon Kahana) (2016), Hemmo references yet another Ofakim Hadashim member. Kahana, in an unlikely move for an Ofakim Hadashim member – the group was strongly associated with shaping the Zionist ethos – comments on the recent War of Independence in his works from 1948. As with her dust works, the material chosen for recreating the image causes it, at the same time, to disintegrate. Hemmo isolated a fragment from Kahana and recreated it on a monumental scale. Further, by positioning the image sideways, the figure of the soldier – now thoroughly blackened – gains in eroticism.

Whether by the darkening by charcoal or the imminent dissipation of dust, in Hemmo’s hands the constitutive substances become political, operating altering states of positive and negative on their precedent. Furthermore, the choice of working with a material that is constantly subject to clean up and removal, echoes Hemmo’s engagement with artists from the margins of the Ofakim Hadashim group, and to an extent of the canon of Israeli art. By reworking the specters of art historical precedents she rewrites a history of absence, silencing, recollection and erasure.

-

Before the counting of time had begun, since the dawn of civilization, humans stood on Mount Mihya, breathed the dust of roads between Avdat and the Zin River, and painted. The rock petroglyphs engraved on desert rocks are the oeuvre of ancient cultures. The patina of limestones found in the Negev Desert carry images of gazelles, bulls and lions – etched during the bronze age; camels and fertility symbols – from the Nabataean period; and territorial and other inscriptions from the Arab period. In the past 6000 years these rocks have been carrying shapes and words in ancient languages, presenting an evolution of etchings and drawings, a graphic archaeology of customs, cults, politics and culture.

Making his way on the flint gravel of a desert pavement, Gaston Zvi Ickowicz is an attentive wanderer among the dark-hued rocks that loom above the ground. Ickowicz photographs the rock petroglyphs lying under the desert sun, the reddish skin of the slabs and the rocky folds torn open by time. In a close-up he captures the image of a gazelle: inscribed on a shaded corner of the rock she is protected, closely verging on neighboring rocks. The close-up, piercing deep into this contingency, is revelatory of the processes that have shaped this desert landscape, the footprints of geological transformations in the stone’s hue and density.

Ickowicz’s looks at this landscape to see the signs left behind by the history of men and the phenomena of geology alike. He calls attention to a nature whose working have split several petroglyphs, once residing side by side on the same surface, into the parts of a triptych; he shows how it is nature that has determined the coloration and the alteration in intensity, from dark tones to bright.

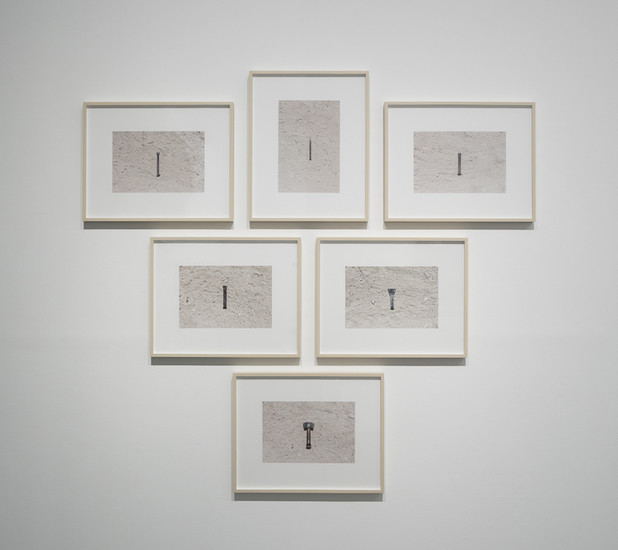

A grey cloud of stone particles covers the ground of Rawabi, a Palestinian city being built north of Ramallah. Ickowicz had laid on its ground the work tools of a stonemason’s, capturing them with the dust emanating from a traditional stonemasonry that is still practiced by hand. Captured together, the tool is linked to the ground, in a way that points to the gap between the manual labor exercised and the modern city being built with it. As with the rock petroglyphs, these too are the manufacturing tools of a new culture, they are communicative objects that carry a symbolic and political charge.

A series of photographs taken by Walker Evans in 1955 shows work tools, some of which identical to those found in Ickowicz’s photographs as well. Evans shot his tools brand new, on a neutral backdrop. Those of Rawabi’s stonemasons, however, have witnessed injuries, blisters and peels. Ickowicz allows the tool to appear in conjunction with its cultural and symbolic context, summoning in the realm in which it is given in its totality – the city of Rawabi, the hands that have handled it, the blows dealt to it by time.

-

In the Fayum necropolis of ancient Egypt, just as the Western timeline had begun, it had been custom to display, in front of the burial caskets of mummies, a realistic portrait of the diseased, part of a long tradition of painting on wooden panels or linen. One of the techniques that had been in use involved a mixture of beeswax with pigments, also known as Encaustic. The portraits brought detailed depictions of the faces of Fayum dwellers, especially from an urban middle class. [4]

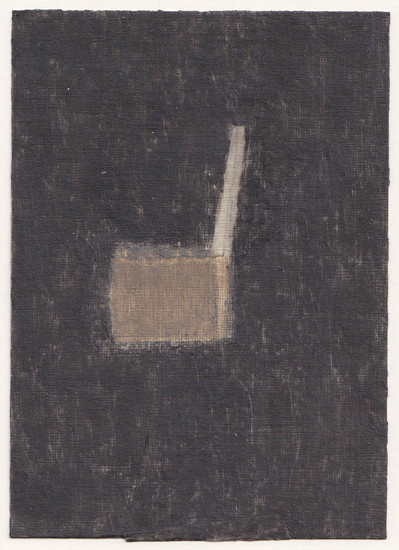

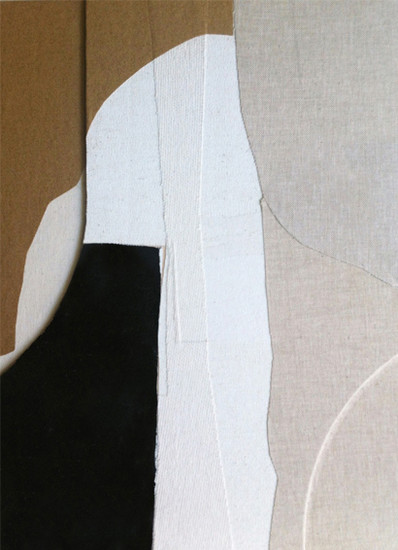

Drawn to the materiality and texture of the Fayum portraits, Sharon Etgar uses the same traditional technique but forfeits the facial features of the departed for abstract, archaic-looking shapes. Following her reading of poet T. S. Eliot, she produces disorienting landscapes of unclear identification – “Time present and time past / Are both perhaps present in time future / And time future contained in time past.” [5]

Etgar’s abstract collages address the interplay arising between the shapes. The forms are translated from fragments of real-life experiences, from memories and sensations related to nature or to the imagination. Departing from the context of objects within their surrounding, she extracts lines as they manifest themselves in the contingency of their borders. A similar process takes place in her work “Night I,” which hints at the encounter of celestial bodies with the landscape. These fabric works recall the role culture reserves to various coverings as markers of place – as, for example, with blankets enveloping the body as a way of delimiting an area intimacy, or the prayer rugs used in religious worship.

Etgar treats these materials through their infinite potential of unraveling. Each of her fragments – whether textile or paper – can be traced back to the leftovers of a previous work or to a work not brought to completion. Etgar’s shapes are the shreds and residues of larger elements – of shapes that likewise have been isolated from a larger, previously existing support, fragments that have been isolated from a broader realm of possibilities. The selected cutouts and elements appear as archeological finds still in the digging, of concealment and uncovering. The fabric support allows us to trace her handiwork throughout the steps of its progress. One layer of fabric conceals another, one seam overrides another.

Text: Ilanit Konopny and Karine Shabtai

1. Miriam Chalfi, “Stone,” in: Silent Voices, Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishers, 2011. (In Hebrew).

2. Gideon Ofrat, “The Fire,” in: The Jewish Derrida, trs. Peretz Kidron, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2001, pp. 94-95.

3. Yigal Zalmona, 100 Years of Israeli Art, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 2011.

4. John Berger, “The Fayum Portraits,” in: The Shape of a Pocket, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2001 (unpaginated).

5. T. S. Eliot, “Burnt Norton,” The Four Quartets, Orlando: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014, p. 19.