Hunting West

Rami Maymon, Shay Zilberman

Inga gallery is proud to announce the opening of the shared exhibition of the artists Shay Zilberman and Rami Maymon.

The exhibition ‘Hunting West’ was born from an ongoing dialog between the two artists. At the root of their common work are art publications and catalogs, which serve as sources and material. The books are deconstructed in a multi-faceted process and reconfigured as a collage. The gallery space acts as one organ divided into two rooms, as a heart is divided.

Shay Zilberman (left room)

The book of Genesis tells the story of forty days and nights in which a microcosm tossed back and forth in the belly of Noah’s Ark, between ״the fountains of the great deep and the open windows of heaven.״ At the end of these forty days, the chosen, protected universe ended on top of Mount Ararat.2 There, Noah opened the Ark’s window for the first time, ״and sent forth a raven, which went forth to and from, until the waters were dried up from off the earth.״ Like a messenger unable to complete his mission, the raven kept flying in circles around the ark. Was it banished or did the hatch open to let it back in after flying over the primordial chaos? By then, ״Noah already sent forth a dove from him, to see if the waters were abated from off the face of the ground. But the dove found

no rest for the sole of her foot, and she returned unto him into the ark, for the waters were on the face of the whole earth, he put forth his hand, and pulled her in unto him into the ark״. The dove went back and forth, covering a great distance until finally she delivered the news: an olive leaf. And the raven?

As the man flung open the shutter to the tapping wind, he discovered the Raven, Dark and stately, as old as ״.a grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird3״ time, the ebony Raven in Edgar Allen Poe’s poem flew through the window and into the room, where he ״perched upon a bust of Pallas just above the chamber door — Perched, and sat, and nothing more.״ The Raven stood motionless on top of wisdom, art, and justice. The man tries to plead with the fowl: ״Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore! ... Leave my loneliness unbroken! — quit the bust above my door!״ But the raven does not move, and to each question responds: Nevermore. Yearning to reunite with his dead love, the man looks for words of wisdom from the Raven, trying to decipher the prophecy of his croak: Nevermore. And so, the raven stands on the threshold, as a guardian that comes between the souls of the living and the dead, stopping the man’s journey to oblivion.

The door opens to reveal a raven, white as a dove. Materialized in porcelain, she stands in the gallery like the negative of her black feathers. According to Ovid, the ״Raven had once been a bird of silvery-white plumage, so that he rivalled the spotless doves, nor yielded to the geese which one day were to save the Capitol with their watchful cries, nor to the river-loving swan.״ But his tongue was his undoing. The bird’s habit to speak ill led to a divine punishment and changed its form. ״Thy plumage, talking raven, though white before, had been suddenly changed to black4.״ In a renewed metamorphosis Shay Zilberman restores the raven’s white color. He casts her in her former glory, bringing to mind the Tang Dynasty tradition of pottery tomb figures in human or animal shape, placed as tomb guardians who protect and accompany the dead on his journey. In an ongoing transformation from good to bad and back to good — as a mythical symbol of hell and evil, the harbinger of death or a sacred bird, goddess of war and wisdom — the raven is enveloped by contrasting meanings drawn from legends and mythologies of different cultures.

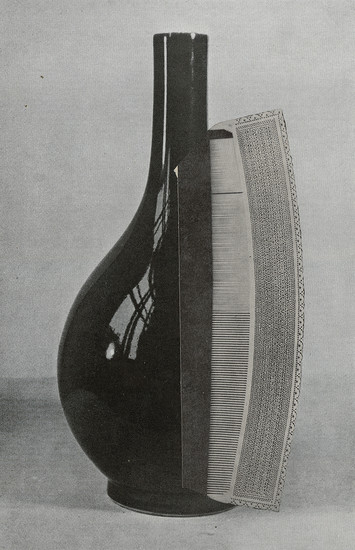

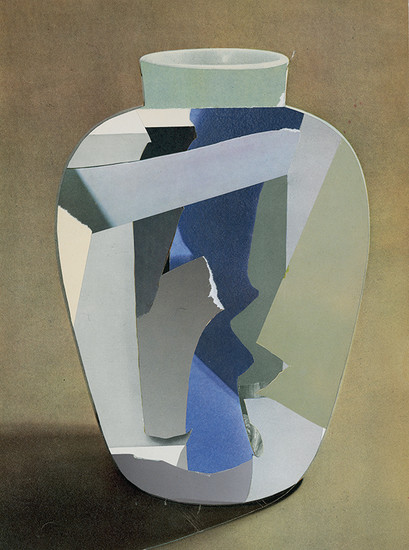

When they sailed out to conquer new lands, seas, and trade routes in the 16th century, Portuguese ships carried valuable porcelains from China to Europe. They led the migration of porcelain to the West. Originating in early Chinese dynasties, porcelain was woven and integrated into local European ceramic traditions. The pages of a British textbook about porcelain vases techniques from the second half of the 20th century are spread across the wall of the gallery. Like a master cartographer, Zilberman liberates the heart of the porcelain vases, leaving outlines and outer borders and reconstructing topographical layers. Using collage technique, he empties or covers the walls of the porcelain vases from Eastern and Western countries, ancient and later periods. The inside of the vase, a two-dimensional photograph, gains a second life as three-dimensional and multilayered, swathed in shrouds from new worlds: textures and shapes drawn from ambiguous photographs, taken out of books and catalogues from the artist’s collection. The vases, as receptacles, as chests that hold the entire world, as urns in the dead’s journey to eternity — just like the raven, in different shapes and colors. From the flight of the bird across the pages of the book, a black and white surface, a new window opens to reveal a depth of field in its multitude of colors.

Rami Maymon (right room)

The Book of Genesis tells the story of a damsel who stood holding a jug on her shoulder by a water well. When the servant approached her and asked: ״Let me, I pray thee, drink a little water of thy pitcher — Rebekah made haste and let down her pitcher from her shoulder, to quench his and his camels’ thirst.״ In biblical paintings, her pitcher stands for the pitcher of life, plenty, and eroticism, and the well is a fertile womb. This identification of the Orient with the image of a pitcher and of the pitcher with women expanded in 19th century Orientalist painting and photography. In 1920s Italy, drawing on the restored connection with the Roman past, the ׳Novecento׳ painters viewed pitchers as a symbol of the human condition, a reflection of the human figure — while highlighting Roman architecture, sculptures, and vases. Israeli art during the 1940s was split between the camp of artists “who are not afraid of the jug (among others) and also identify the Orient with the jug, and the artists of abstraction, who strive to merge in international language of forms that negates local content,” and reject the Arab jug motif. However, “the big revolution was in the Postmodern trend of the 1980s. This is the trend where the vase of life has changed into the vase of death, from the vase of Eros to the vase of Thanatos, from the water pitcher to the urn.”5

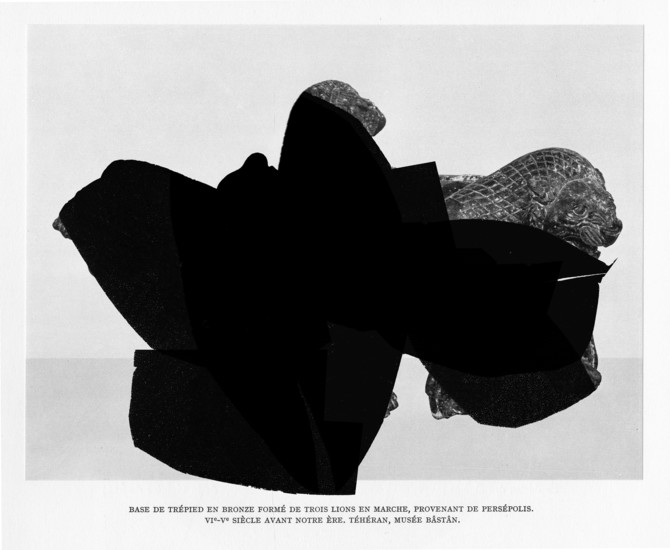

The visitor who steps over the threshold and enters the heart of the gallery’s right side, comes face to face with Rami Maymon’s eastern wind. As he looks at an abstract blue geometric shape or reads the inscription “A girl holding a water Jug, ca. 1880, private collection, Paris,” his mind conjures up the dormant Orientalist figure on the stitched and stretched fabrics. While absent and expropriated from the pages of a book, the image endures in its living-dead state through collective memory, through the history of abstract art in its local context. In the early second millennium BC, Babylonian clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform writing recount ׳The Epic of Gilgamesh׳ — the fifth king in the Sumerian dynasty: ״Gilgamesh, dazzling, sublime. Opener of the mountain passes, digger of wells on the hills’ side.״ He asks Utnapishtim, the hero of the Akkadian flood story who like the biblical Noah saved mankind from extinction, to tell him how he was granted eternal life in the Garden of the Gods — the Sumerian paradise. Ea, the god of wisdom and magic, suggests that the Gods who punished all of mankind, destroy only the sinners: ״Instead of your bringing on the Flood, let lions rise up and diminish the people.6״ In Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, lions were considered the guardians of the gods, and statues of lions often flanked the entrances to temples. In the 1930s, in the Land of Israel, Abraham Melnikov sculptured the Canaanite style Lion of Judea in commemoration of the casualties of the battle at Tel Hai, inspired by Assyrian lion reliefs. The lion, who raises his head to the sky with a roar, faces east as a symbol of “the rebirth of the historical Hebrew nation,” and a political allusion to “the idea of Jewish domination over both banks of the Jordan.”7

The eye of the visitor to the gallery’s inner space travels between a Persian sculpture of a lion, an Egyptian tomb, a biblical jug, a Canaanite desert. These were coated, shielded, defaced with layers of colors and shapes, obstructions and openings from other sources. In stitched, glued, two-dimensional and three-dimensional collages, they intermingle with French Orientalism and sculptural Modernism. Maymon disrupts the observation of the entire, purportedly original, image, leading it on a journey from the figurative to the abstract. He sculpts a pair of black monoliths that were placed on plinths, covering the objects or the space trapped inside them, like an imagined archeology museum.

In a reversal of Melnikov’s declaration that “East and West are distant from each other and neither makes contact with the other even when they meet”8 — Maymon looks for dialogues, metamorphoses, and hybridizations of Eastern and Western representations. He walks among the pages of art history books, books of local and universal shapes and images. In an act of tribute and vandalism, Maymon intervenes, distorts, highlights, and downplays photographic objects to form collages, returning them to the photographic medium. The collage is enlarged as a wallpaper, as photo paper, divulging the intimate details and the archaeological strata of the artistic act. On the immense collage lies a single, direct formalist photograph, divided into light and shade: two black birds with white heads, facing one another as in a ritual of offering exchange or ancient trade with stone-age tools: one presents an elephant's tusk and the other — a sharpened flint axe.

From its place on the gallery wall, the eye of Nefertiti hovers above the entire space, like the eye of Ra, the sun god who guards the capital of the kingdom in Egyptian mythology, or a symbol that wards off the evil eye. The eye of Nefertiti as a metronomic representation of beauty and perfection, as a talisman for a good life — makes its way from archeological sites in Ancient Egypt to a postcard from a German museum, taped to a piece of cardboard picked up on a Greek island. The journey of Maymon’s eye East and West is one that has no hierarchies, an ongoing state of becoming and migration from the ancient, to the contemporary, to the ancient.

Text by Ilanit Konopny

1. The exhibition’s title was inspired by Rabbi Yehuda Halevi’s poem On the Sea.

2. Itzhak Benyamini, “The Flood” in Abraham’s Laughter: Interpretation of Genesis as Critical Theology (Tel Aviv: Resling Publishing, 2011), p. 59–72 (in Hebrew).

3. Edgar Allan Poe, The Raven, 1845, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48860/the-raven.

4. Ovid, Metamorphoses vol. I, with an English trans. by Frank Ju us Miller (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1916), pp. 97–105..

5. Gideon Ofrat, “The Eros Vase and the Urn” in Within a Local Context (Tel Aviv: Kibbutz Mehuad, 2004), pp. 252-258, (in Hebrew).

6. John Gardner and John Maier, Gilgamesh (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing, 1985).

7. Yigal Zalmona, "Moderni s and the Fascination with the Ea " in A Century of Israeli Art (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 2013), p. 61. 8. Ibid., p. 56.