Force Majeure

Motoi Yamamoto, Gaston Zvi Ickowicz, Inge Pries Kantor, Ibe Kyoko, Francisco Vidal, Neta Harari, Ali Silverstein, Angela Klein, Netta Lieber Sheffer

Force Majeure

Group exhibition

-

Opening event: Thursday, December 5th

Closing event: Saturday, January 18th

-

Force Majeure is a contractual term, used most commonly in the domains of law and insurance to describe enforceable events imposed on people without their control or initiative, thus preventing them from fulfilling a contract. Natural events like tsunamis strike villages, cities, and power plants, paralyzing entire regions. Man-made events like guerilla and civil wars devastate societies, turning the lives of citizens upside-down.

Ripped from their possessions and loved ones, the path for rehabilitation for many of the victims of such events involves migration; a search for a new source of life in unfamiliar territory.

The artwork in this exhibition investigate different catastrophes, natural or man-made, that were imposed on their subjects.

The exhibition kicks off with Angela Klein’s Red Button, portraying a missile lunching button that can lead, with one press, to the widespread destruction of humans and nature.

Next, Hajj by Gaston Zvi Ickowicz depicts a wall in the Muslim Quarter in Jerusalem’s Old City. An Innocent looking wall where pilgrims returning from the holy site of Mecca mark and commemorate their journey, could be interpreted as a benign celebration of the completion of a religious duty, but also as the public display of religious zealousness.

Fed up with war, Angola based artist Francisco Vidal returned to the turmoil and conflict of his homeland, where he appropriated the machete as an unusual platform for his artwork. The machete was used by rebels during the civil war that took place in Angola from 1975 to 2002. In Vidal’s work the machete is covered with layers of neon colors (representing motifs from the war), over which the word “free” emerges.

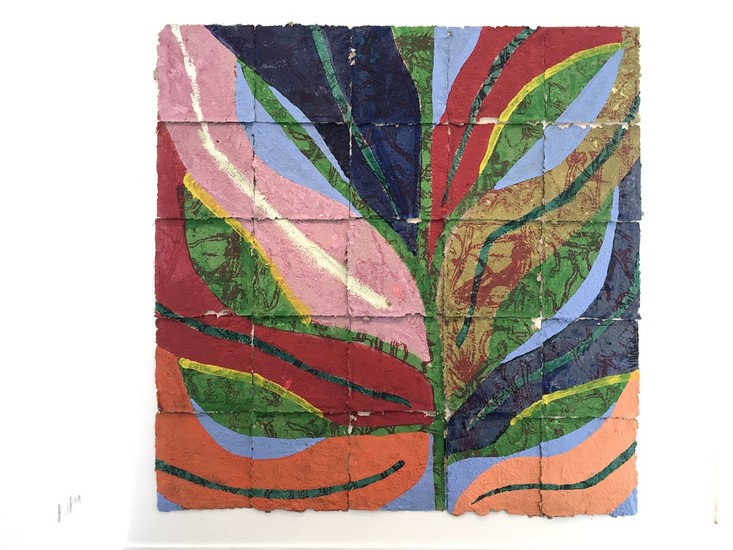

In a large drawing spread over a series of paper squares, the cotton flower appears. A recurring motif in Vidal’s work, the cotton flower carries deep symbolical meaning in Angola. It symbolized the early anticolonial resistance in Angola (1961), which was sparked by cotton field workers protesting the conditions imposed on them under a regime of slavery. This resistance led to a long and bloody war of independence from the Portuguese control over the country (1975).

Francisco Vidal’s work draws on the history of Angola in the past decades, the fight for independence and the civil war that followed. At the age of 30, Vidal moved to the capital Luanda, where the restricted access to material and workspace shaped the nature of his art. Vidal is inspired by the legacy of the Bauhaus school (“the artist, the craftsman, and the technician, combined in one”) which sought to promote social and political reforms in art, design, and everyday life. Vidal developed a modular machine that allows him to produce squares from recycled paper. This machine functions, in a sense, as his portable studio.

Inge Price Kantor observes Africa from her vantage point in Germany. She documents African men and women making their way: some fleeing, some voyaging; perhaps aiming to resettle in Europe, perhaps just resettling their thoughts in a western mindset, as they shed their color, clothes and convictions.

As is always the case in Price Kantor’s work, her characters are not monosemic, nor do they lend themselves to political exploitation. Marked by tragic-comic scenarios, Price Kantor’s work renders a modern version of the Ship of Fools, sending her characters on an absurd odyssey of mistakes and misgivings.

Neta Harari Navon deconstructs social and personal orders. Employing a multidirectional gaze, she introspects her crumbling life and inspects a fissured, combative, society. The destruction of the private home begins with the destruction of the homeland, national chaos penetrates the private sphere, her warrior charges with his sword drawn and ready for battle. An image for this work was taken from a series of photographs by Ziv Koren who documented the evacuation of the Amona settlement in 2006 .

Ibe Kayoko created a paper partition following the tsunami that devastated Japan in 2011. Ibe’s family lives in the Fukushima region, which was hit by the storm. The paper partitions capture the raging ocean, its unforgiving depths, and the emotional turbulence that remained in the hearts of residents in the storm’s aftermath.

Motoi Yamamoto explores death in his art. His pencil drawing was created in preparation for a special installation of salt whirlpools that he created for museums and galleries around the world. The whirlpool, swirling black and white tones, symbolizes beginning and end, birth and death. An endless life cycle is absorbed into the wood to which Yamamoto glued the drawing, wrapping both with a thick layer of Japanese varnish, giving the drawing the semblance of marble. Perhaps a tombstone?...

Natural and man-mane whirlpools also appear in the works of Gaston Zvi Ickowicz .

Zvi Ickowicz photographed wind whirlpools ascending above the ruins of abandoned villages in the Gaza Envelope. As in the work of Yamamoto, the combination of black and white forms an ephemeral mass hovering above areas of destruction, replacing the hollowed presence of humans. Zvi Ickowicz studied the torched land created by explosive kites and balloons launched from Gaza towards the Jewish communities of the Gaze Envelope. This torched land exposed and highlighted the ruins of abandoned Palestinian villages Simsim, Najd, and al-Mansura. These ruins mark an eternal reminder of the lives of the village dwellers who fled and exiled from their land.

Netta Lieber Sheffer created a house trailer, providing a cramped, yet portable living space – perhaps as a way to prepare for catastrophe, perhaps as evidence that it already took place. A trio of riders tied to one another, like Inge Price Kantor‘s self-designated abductors, ride towards an unclear partnership.

Ali Silverstein concludes the exhibition with the forces of nature – an imaginary mountain towering above us, with precipitation or lava dripping above it.

As part of the exhibition’s opening event, the Japanese calligraphy artist Tumoko Kuwan will perform a live drawing which will remain in display on the room’s floor. The calligraphic design centers on the word SUSUMU. The word, consisting of the word “journey”, means progression, moving on, promoting others and helping them reach better places.